On a Scale of 1-10, How Much Faith Do You Have in the Federal Reserve?

Personally, 0

The credibility of the Fed is a topic often canvassed by many in the finance community. Most believe that the Fed has done a sufficient job given the once-in-a-century pandemic we entered at the start of the decade, while others believe that they’ve continuously committed several policy blunders and are consequently devoid of any credibility. I believe that the latter is closer to the truth, and it is empirically evident.

“No major institution in the US has so poor a record of performance over so long a period as the Federal Reserve, yet so high a public reputation.”—Milton Friedman

In 2020 when the advent of COVID shocked the world, the Fed (and several other CBs) acted promptly to mitigate sell-offs and abate fears. In unprecedented fashion, QE & fiscal policy combined to support financial markets and spur spending. These are things that the majority are already privy to. But what they have either completely overlooked or trivialized is that the initial coordinated policy error (Fiscal & Fed) incited further coordinated policy errors.

The moment unprecedented fiscal profligacy and monetary policy neglect merged; America found itself vis-à-vis with a painful reality; a concept reminiscent of the 70s. Because moderation is foreign terminology to policymakers (and Americans generally), profligacy is an inherent quality of policymaking. Knowing this, one can come to the conclusion that since monetary policy was too accommodative for too long, it will be too contractionary for too long.

The aforementioned policy error of ‘20-’21 was the first major policy error of the decade. The second was the Fed’s failure to get ahead of the curve after witnessing unbridled spending. Continuing ZIRP and expanding their balance sheet in spite of 40yr highs in inflation wasn’t a mistake. It was willful negligence. This monetary policy neglect induced the simultaneous creation of the “everything bubble.”

“The real danger comes from [the Fed] encouraging or inadvertently tolerating rising inflation and its close cousin of extreme speculation and risk taking, in effect standing by while bubbles and excesses threaten financial markets,” Volcker later wrote in his memoir.” —The Fed’s Doomsday Prophet Has a Dire Warning About Where We’re Headed - POLITICO

Sound familiar?

“And now, for the first time since the Great Inflation of the 1970s, consumer prices are rising quickly along with asset prices. Strained supply chains are to blame for that, but so is the very strong demand created by central banks, Hoenig said. The Fed has been encouraging government spending by purchasing billions of Treasury bonds each month while pumping new money into the banks. Just like the 1970s, there are now a whole lot of dollars chasing a limited amount of goods. “That’s a big demand pull on the economy,” Hoenig said. “The Fed is facilitating that.”— The Fed’s Doomsday Prophet Has a Dire Warning About Where We’re Headed - POLITICO

While the current inflationary period is undoubtedly reminiscent of the 70s, it’s pivotal that we don’t use history as a roadmap for the future in this instance. Stop-n-go policy begot higher and exceedingly volatile inflation in the 70s. In our current circumstance, we have no wiggle room to make this same mistake. This leads me to highlight the third major policy error from the Fed.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes. In lieu of repeating the stop-n-go1 catastrophe, the Fed, after hiking rates at a historic pace to combat inflation, decided to not only slow the pace of rate hikes but also neglect FCI easing. Since November & December’s inflation prints were cooler than expected, the Fed felt emboldened to declare that disinflation was taking place, and that they were satisfied with this development.

A number of participants observed that, as monetary policy approached a stance that was sufficiently restrictive to achieve the Committee’s goals, it would become appropriate to slow the pace of increase in the target range for the federal funds rate. In addition, a substantial majority of participants judged that a slowing in the pace of increase would likely soon be appropriate. A slower pace in these circumstances would better allow the Committee to assess progress toward its goals of maximum employment and price stability.

A few participants commented that slowing the pace of increase could reduce the risk of instability in the financial system. A few other participants noted that, before slowing the pace of policy rate increases, it could be advantageous to wait until the stance of policy was more clearly in restrictive territory and there were more concrete signs that inflation pressures were receding significantly.

Given that the minutes were released after an exceedingly cool October CPI print, this tone would be justifiable to most. Financial conditions had tightened considerably at this point, but it was this same laxity towards the pace of rate hikes that would allow for the unwarranted easing of FCI, driven by a misunderstanding of the Fed’s reaction function.

Participants noted that, because monetary policy worked importantly through financial markets, an unwarranted easing in financial conditions, especially if driven by a misperception by the public of the Committee’s reaction function, would complicate the Committee’s effort to restore price stability.

By the time these minutes were released market participants were already taking premature victory laps. Some “experts” declared inflation to be dead shortly after this. FCI eased significantly as the data dependent Fed sounded more dovish by each passing day. FOMO & complacency were distinctly pervasive mindsets during this period.

Then came the February FOMC meeting.

“I would put it this way. It’s something that we monitor carefully. Financial conditions didn’t really change much from the December meeting to now. They mostly went sideways or up and down but came out in roughly the same place. It’s important that the markets do reflect the tightening that we’re putting in place. As we’ve discussed a couple times here, there’s a difference in perspective by some market measures on how fast inflation will come down. We’re just going to have to see. I mean, I’m not going to try to persuade people to have a different forecast, but our forecast is that it will take some time and some patience and that we’ll need to keep rates higher for longer. But we’ll see.” — Powell

This was in response to a question regarding whether or not the concern towards the unwarranted easing of FCI was still prevalent. The following day, the highest call volume ever was recorded. It was clear that Powell had made yet another policy error.

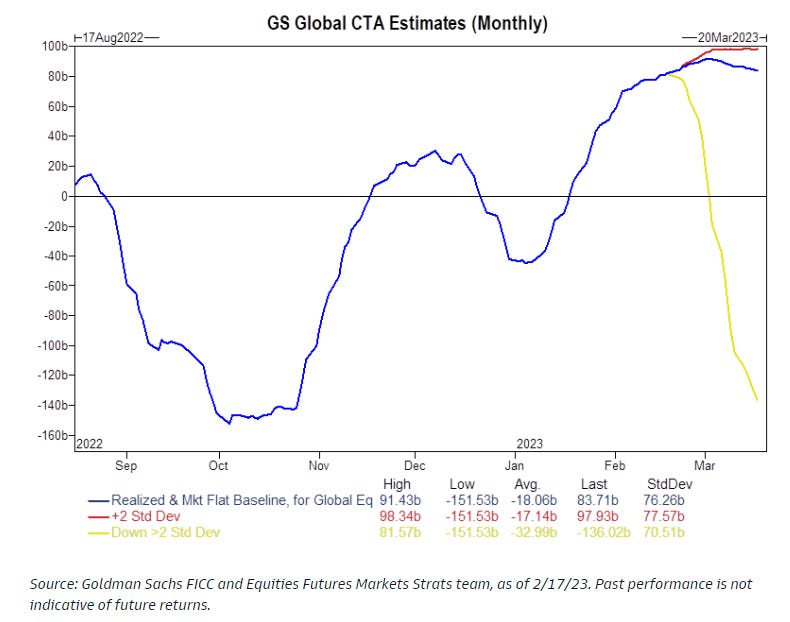

And CTAs were offsides as well (they still are). No surprises here.

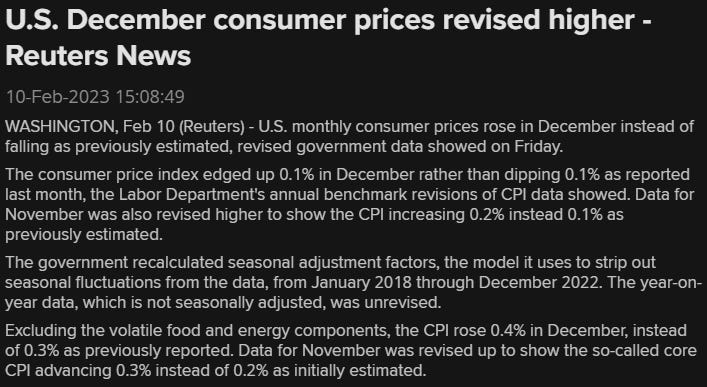

The market received a bitter truth a little over a week later. Amidst a market that began to exhibit a similar ebullience seen in early ‘21, November & December’s inflation data was revised higher.

Almost every inflation measure for January came in hot following this revision. February 10th felt like a major inflection point. The proverbial nail in the coffin for the disinflation narrative would soon follow.

Participants observed that financial conditions remained much tighter than in early 2022. However, several participants observed that some measures of financial conditions had eased over the past few months. A few participants noted that increased confidence among market participants that inflation would fall quickly appeared to contribute to declines in market expectations of the federal funds rate path beyond the near term. Participants noted that it was important that overall financial conditions be consistent with the degree of policy restraint that the Committee is putting into place in order to bring inflation back to the 2 percent goal.

This is a fairly drastic change from Powell’s last dismissal of FCI easing since October. Data dependency has its pros & cons, and its cons were certainly put on display here. The most influential CB in the world shouldn’t be flip-flopping due to data dependency when it’s already firmly behind the curve.

Since then, Powell has only been increasing in hawkishness, throwing out comments such as, “the peak rate in the next dot plot may well be higher than December.” This is a salient comment because the recent ebullience in the market was in large part due to the Fed’s failure to swiftly refute the erroneous claim that inflation would be sitting at 2% by June with rate cuts following shortly after. This view was consensus and obviously a pipe dream. You can consider this to be the fourth major policy error.

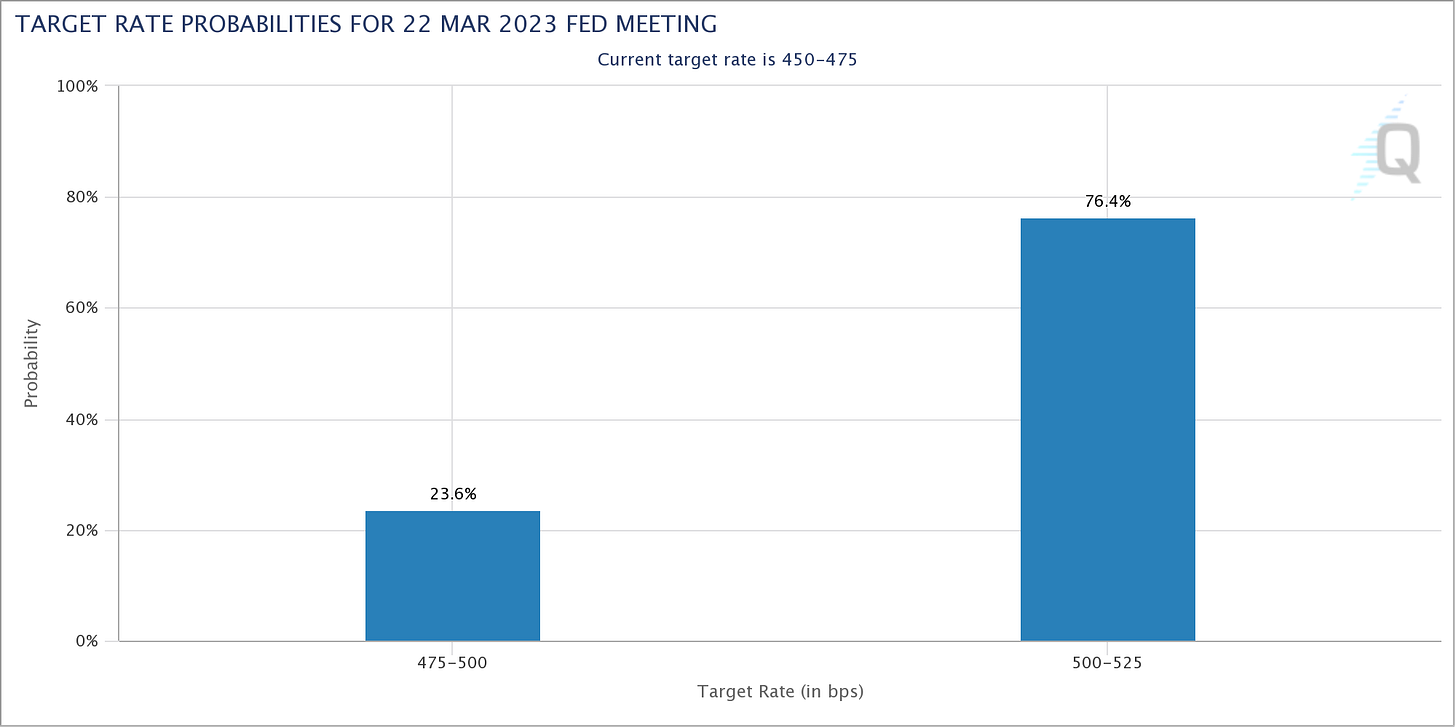

In fact, it was so egregious that the Fed, if incoming data encourages it, will increase the pace of rate hikes again. And the odds of this happening are increasing by the day. A month ago the odds of a 50bp hike at the March FOMC meeting were as low as 9%. That was a few days before the revisions in Nov & Dec’s inflation data. The current probability of a 50bp hike later this month is shown below.

Now the $, yields, and rate vol’s paths are becoming more transpicuous. Inflation expectations are rising as well.

And the higher for longer mantra is starting to gain some traction. Since rates have risen considerably since early February, they (particularly the short end) do have some room to cool off here for a bit in the near future. The bear steepener will probably rear its ugly head this year, putting more downward pressure on equities, and marking the bottom in the UR.

Lastly, I’d like to highlight Powell’s remarks pertaining to China’s reopening from December and March.

December FOMC Presser:

“Weaker output in China will push down on commodity prices, but it could interfere with supply chains ultimately. And that could push inflation up in the West. It’s very hard to say, you know, how much—how those two will offset each other. And it doesn’t seem likely, actually, that the overall net effect would be material on us.”

Powell’s Testimony Before Congress:

“China’s faster reopening could put upward pressure on commodities prices but also quicker healing of supply chains.”

The messages are strikingly similar and seem to be devoid of any concern towards geopolitical induced exogenous shocks to the commodity space. Even with the absence of an exogenous supply shock, the resilience of the labor market coupled with China’s reopening is helping to reignite inflation concerns.

The manufacturing sector saw its biggest improvement in activity in more than a decade in February and consumer activity climbed, the latest purchasing managers’ surveys showed. Chinese housing sales also rose for the first time in 20 months, according to data from the 100 biggest real estate developers.

The economic outlook remains uncertain, though, against the backdrop of weak global growth and rising interest rates. Demand for Chinese exports from some of the country’s biggest markets like the US and Europe have plummeted in recent months and are likely to remain weak this year. US-China tensions over technology and geopolitical matters have also escalated, weighing on business sentiment. —China Leaders Surprised by Pace of Economy’s Rebound - BNN Bloomberg

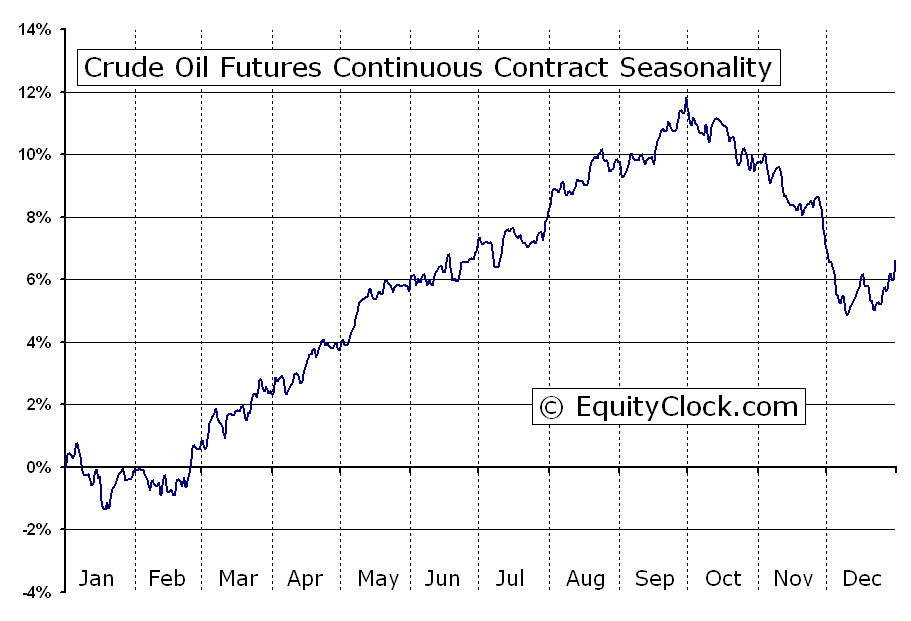

It is true that the economic outlook remains uncertain, but for Powell to trivialize the effect this reopening can have on inflation is incredibly disingenuous. Especially because crude seasonality is on the verge of entering significantly positive territory.

This may be the Fed’s fifth policy error.

All things considered, it’s safe to say that the Fed’s credibility simply doesn’t exist.

The Anguish of Central Banking. Lecture by Arthur F. Burns; commentaries by Milutin & Cirovic and Jacques J. Polak (Belgrade), September 30, 1979 (perjacobsson.org) — an amazing read detailing the ramifications of stop-n-go policy and the efforts that would be required to recover from it.